A route across the history of Cordoba’s Mosque-Cathedral

To enter a building and have your jaw drop is not, at least for us, an everyday event, but every time we enter Córdoba’s Mosque-Cathedral exactly that happens to us. Some places in the world take you back to times past and this one is among them. There is no effort needed here in order to imagine how the building was hundreds of years ago because, as soon as we step in, we already feel transported to the past.

These days pictures are taken of almost everything and then shared on social media to be consumed by millions in a matter of minutes. All information is contained in our mobile-phones and those are within our hand’s reach. This is why it is becoming harder and harder to experience the “tourist’s astonishment”, that is, an emotional alteration caused by the unexpected or unplanned. We all have explored countless places, from home, and we have allegedly already become acquainted with them just by using our all-mighty finger to press “like”. And how often have we heard travelers proclaim “Oh, I have already seen this!” when encountering in person monuments that were expected to surprise them.

And then there are places like Córdoba’s Mosque. And how lucky are we for having them!

And then there are places like Córdoba’s Mosque. And how lucky are we for having them!

Its history as swiftly told.

Muslims started shaping the mosque from the VIIIth c. CE on in several phases, starting from the previously existing Visigothic basilica of San Vicente. The most prominent of such phases encompass the reign of Abd al-Rahman I, Abd al-Rahman II, Al-Hakam II and Almanzor.

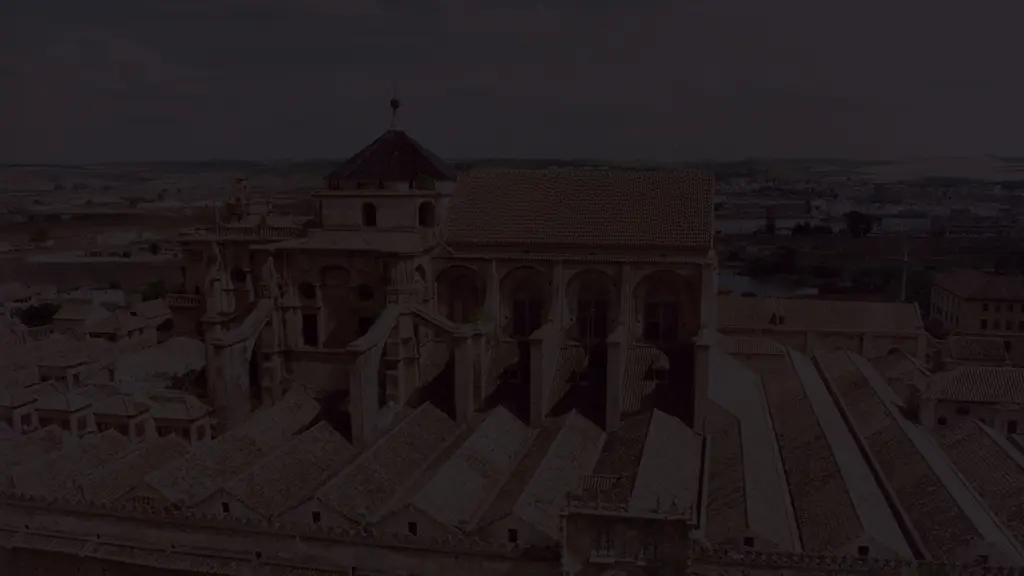

Since 1236, when Christians took the city of Córdoba, many alterations were enterprised resulting (if we add also the refurbishing of the XVI c. when a great nave was erected at the center of the mosque) in the structure we see and marvel at today.

It is precisely this mixture of Islam and Christianity which impacts us the most in this building. There are many mosques and many cathedrals, but to find a structure which integrates both of them traveling to Córdoba is needed. Thus, whether you always wanted to visit it or you had not yet written it on your “must-see” list, we are here to tell you all about our route across the history and features of this place, named “Of Cultural Interest” and World Heritage Site by the UNESCO.

Memories and features of an unusual place.

We better have, first, an idea of the component parts of this complex, which can be divided in three big areas: the old minaret (nowadays a bell-tower), the courtyard and the praying room.

The old minaret

The courtyard

Standing at 54 meters the tower is the highest of Córdoba buildings. It was a minaret for calling Muslims to prayer since Abd al-Rahman III, yet it had to be repaired several times (and most acutely in 1593) and became finally the Baroque bell-tower we see today. It may come as a surprise to tourists that even today remnants of the original minaret are found in its interior.

The courtyard is nicknamed “Court of the Orange-trees” due to the 98 trees of this species which stand throughout it since at least the XVIIIth century. This enclosed 130 x 50 meters space contains two great fountains and three water jets. The original courtyard was constructed during the reign of Abd al-Rahman I as a ṣaḥn (that is, a patio for the ablutions mandatory before prayer). It was expanded with Abd al-Rahman III and again with Almanzor, who also built a well therein so that the faithful did not run out of water while practicing ablutions. The porched galleries which surround the courtyard have been used in multiple ways across the ages, as a school, a tribunal, an orphanage, a hospital…

Lastly, the praying room greets us with the realization that visiting its surface of 23,400 m2 is not going to be an easy task.

As a curiosity we can mention the age-old question of the “erroneous orientation” of the miḥrāb (that is, the praying wall) here, which goes on unresolved until today. According to Islamic tradition the miḥrāb ought to be oriented towards Mecca, yet Córdoba’s, as several other early mosques’, faces elsewhere. Scholarship varies on the reason why (special requisites of the terrain, a quirk of the Umayyads…) but no explanation has convinced all within the field, so we will not try to resolve the matter here either.

Throughout our itinerary the first thing to call the attention of visitors at the Córdoba mosque is its vastness: with 1300 columns holding the world-renown 365 red-and-white arches, it all appears diaphanous, great. While sauntering the old part of the Mosque-Cathedral it will perhaps surprise us the lack of homogeneity among the columns’ base, shaft and capital, which is due to Muslims having utilized the ever-so-useful “spolia” (that is, reused building parts) in order to finish their work. Roman and Visigothic pieces from nearby sites were used, saving time and coin, so that the first mosque, the one of Abd al-Rahman I, could be built in about two years and finished by 787, just before the emir’s death.

Abd al-Rahman II (emir from 822 to 852) enlarged the mosque in two stages, albeit respecting the original naves. The columns added at this point lack base and, we now know, were brought from Mérida’s Roman theater profiting from the several raids the emir ordered against that city.

Al-Hakam II (caliph between 961 and 976) enlarged the mosque for the second time and created the most beautiful parts of the building we love today. The marble columns and capitals added at this stage were built specifically for the places were they still stand, the arches reach technical perfection and artisans from Byzantium are called to work on the mosaics. It is at this point that the miḥrāb we see today, considered one of the most beautiful the world over, is built.

It took Almanzor, at the end of the Xth century, to command the biggest extension of the mosque to date, partly because of Córdoba’s growing population and partly because of an ego which pushed him to imprint a personal mark in the building so that it too could stand the passing of time. Technically speaking the works conducted at this stage are not meritorious, since they repeat what had been done previously and arches stop combining white stone and red bricks to form the semicircle, placing limestone all over instead and painting it red in alternation.

The arrival of Christian practices and the cultural mix.

After the Christian conquest the mosque started being used for Catholic masses. A “Main Chapel” was built in one of its corners while the rest of the structure was retained. In the XVIth c. the bishop Alonso Manrique promoted the idea of erecting a Gothic cathedral amid the building, an idea which sparkled a bout of controversy and divided the population either for or against it. It was the Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, to mediate in the conflict and approve such a project’s takeoff, although it is said that he later regretted having planted an “ordinary” cathedral in the midst of a unique building.

The works continued for two centuries and were headed by chief architects who lived in different epochs, resulting in a cathedral with a diachronic mixture of elements, from Gothic arches to Plateresque ornamentation to a Renaissance dome and the Baroque bell-tower with which the old minaret was covered.